Adotas Premium v. Remnant Series

August 10th, 2007

Adotas is also doing a Premium v. Remnant series. In the post Noah argues that:

As brand marketers better understand the level to which they are overpaying for inventory, publishers will face significant pressure to either open up their unsold inventory directly to the brand marketers or to stop selling unsold inventory at the discounts currently allowed.

In general I agree with Noah that the gap in pricing between “Premium” and “Remnant” is too large, but I don’t think there’s any risk to a publisher’s bottom line. If the numbers quoted, $10b for DM and $5b for premium are correct, then only a third of spend is at risk from more efficient brand pricing. Also, the amount of brand money online is growing every year, meaning more competition for inventory and higher rates. I expect both publishers and advertisers to get smarter over the coming years and fewer inefficiencies where “premium” inventory sells for so much more than “remnant” but with the continued growth in spend and technology I don’t expect many publishers to see a drop in overall rates.

I’ve written about this extensively in my Premium v Remnant series, which you can find here — Part I, Part II and Part III.

I’m looking forward to the rest of the series! I do hope though that they would stop referring to non-guaranteed inventory as “unsold”, especially if it’s a $10b market!

Premium vs. Remnant — (Part III — Remnant)

May 16th, 2007

If you haven’t already, be sure to read Part I and Part II first.

We’ve already discussed my two major reasons why we should stop talking about premium vs. remnant, namely:

- Inventory is deemed premium based on the buyer and has absolutely nothing to do at all with the actual ad impression beind sold

- The best techniques for maximizing revenue for publishers are not specific to performance or brand

In this point I’d like to talk about remnant specifically. Namely, looking at recent patterns I expect non reserved inventory to grow at a far faster pace than reserved inventory. Specifically, I think more and more dollars are going to shift from traditional reserved inventory over to unreserved. Here are five reasons why:

1. Brand advertisers are starting to care about performance

All advertisers are realizing how much quality matters. Although brand metrics might be fuzzier than pure conversion metrics, an ad on Yahoo’s homepage will perform better than on a random article page on the New York Times. More and more brand advertisers are realizing that they can efficiently track performance with online media. The challenge is, how do you track performance when there is no direct online purchase? Sure, clicks measure some sort of performance, but a click from one person might be worth far less than a click from another.

As more inventory becomes available, I expect brand focused advertisers to think of more and more inventive ways to track campaign performance. My Coke Rewards is a great example of a traditional brand advertiser tying traditional sales with online performance. I’ve seen these ads everywhere and I’m sure they’re tracking signups and repeat visitors per media buy.

2. You cannot reserve inventory and optimize on performance

Reserving means setting a price before you buy. Setting a price before you buy means that you can’t adjust your price based on how different slices of inventory perform. Although you can track performance with a reserved/premium buy, you cannot easily optimize. Changing pricing will be a manual and slow process.

3. Ad quality differs greatly between publishers

I’ve looked at a lot of data over the past couple years and performance between sites differs greatly. Some sites will literally have 100x the click and conversion rates over crappier sites. Quality impacts price, and this huge differential in price makes it rather difficult to reserve inventory. Tie this with #1 and #2 above and for any advertiser to start buying effectively they are going to have to start pricing based on performance. This means fewer bulk fixed reserved buys and more CPC, CPA and easily adjusted CPM campaigns. As I pointed out in Part I and Part II of this series, whether or not inventory if premium or remnant depends solely on who the buyer of the impression is, not the actual impression. Hence, fewer reserved guaranteed means more remnant inventory.

4. Optimization technologies are getting better

It’s amazing what people are coming up with these days. Optimization technologies are getting a lot of press these days, and it seems that at every Ad-Tech there are a couple dozen new companies with some new cool modeling technology. I’ve worked with a couple of these companies and it seems that every one I talk to is better than the last. As these technologies improve, the incentive to buy based on performance becomes far more interesting than buying a fixed chunk of inventory at a flat rate — hence, more remnant.

5. User-Gen content is growing like crazy

There’s just a plain shitload of user-gen content out there nowadays. Myspace, Facebook, Youtube, Xanga, Photobucket… shall I keep going? Most of this inventory goes unreserved. Everyone is expecting this to grow more and more.

Thoughts

A lot of the arguments above are dependent on my definition of premium as any reserved inventory. Essentially I believe that more and more online buying is going to move towards performance based pricing. This will strike a good blow to the traditional “premium vs. remnant” selling strategies. It’s also about time we start to talk about the marketplace as a whole, no more about two separate worlds.

In fact, I think we should scrap the word ‘remnant’ altogether. Hell, lets scrap the word premium too! Instead of these two, lets talk about — pre-reserved vs. optimized inventory. Or, the forward-contract vs spot-exchange markets. How about relationship vs. performance based advertisers? Anything but premium vs. remnant!

Premium vs. Remnant — (Part II — Demand)

May 14th, 2007

In Part I we discussed some basic economics and then analyzed the aggregate supply curve that we see in online advertising. We also brought to the table one argument against ‘premium’ vs ‘remnant’. In this post we will look at the demand side of the equation and discuss some arguments for and against splitting out the advertiser market.

What is Demand?

Whereas the supply curve modeled all the possible sources of ad-inventory, the demand curve models all the individuals that want said inventory and have the dollars to buy it. There are many different types of buyers out there, and everyone will put them in different buckets. It’s actually quite confusing, some say ‘premium v. remnant’, some say ‘brand v. performance’ and some other will give you 18 different categories of buyers. Big brand, small brand, big performance conscious brand… etc. etc. etc. For the purposes of this post we will stick with ‘premium’ and ‘remnant’. We will consider premium the pre-reserved demand and remnant everything else.

Premium Demand

Typically coming from ad-agencies, premium demand had some very interesting characteristics. As Greg Yardley pointed out in the comments of Part I, it’s not so much ‘premium’ as a ‘forward contract’. What this means is that most will consider premium premium not because it’s special, simply because someone has reserved this inventory before-hand. The majority of reserved inventory goes to — agencies. Agencies want to ensure that they spend all of their allocated budget by the end of the month/quarter, hence they reserve large portions of inventory before hand to ensure they hit their goals.

Because of the nature of agency budgets and reservation systems, short term premium demand is simply a fixed dollar amount . Think about it — agencies get a certain budget to spend for the quarter and fight their hardest to spend every last penny. If they don’t then they’ll have less money to spend next quarter. Now of course agencies will try to get the best inventory possible for the amount of money that they have to spend, but it’s really a battle between publishers as to how big a slice of the premium money pie they can get.

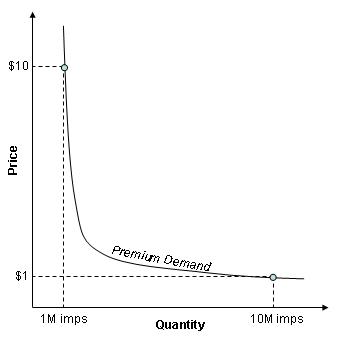

Lets take a hypethetical economy which has premium advertisers that want to spend $10,000. These advertisers will pay a rate that depends primarily on the amount of inventory that is available to them. If the marketplace only had one million impressions available, then the advertiser would buy the inventory for $10 CPM (CPM == Cost per Mille, or price per thousand impressions). That way:

On the contrary, if there were ten million impressions available for purchase then the advertiser would simply pay $1 CPM. That way:

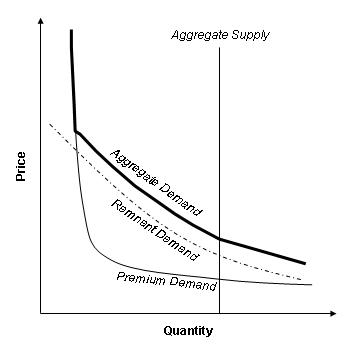

Starting to get the picture? “But Agencies care about performance!!” you might respond…. Well, how do you track ‘performance’ for Ford? Are you going to track the number of cars that people buy online? Brand metrics are fuzzy by nature — people track “aided brand awareness”, “message association” and “brand favourability” (source)! Well — enough words! We can quite easily depict the “fixed $ demand” idea as a demand curve. If we know that $10,000 will go to premium advertisers then as shown above we can calculate the price that will be paid for each possible quantity of inventory. Price X Quality must equal the total dollar demand at each point. If we plot all the points we would get something like this:

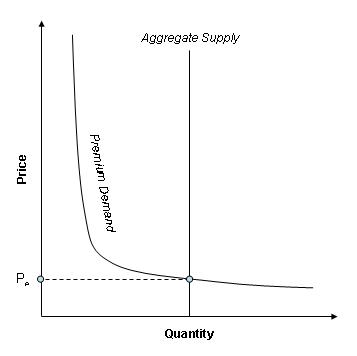

Ok, so now it’s pretty easy to show what would happen in a world where there was only ‘premium demand’, and a fixed amount of short term supply. You’d simply get:

The equilibrium price, ‘Pe’ would simply be the intersection of the ‘premium demand’ and the fixed supply curve. No matter what the quantity is, the total value of the market stays the same — it’s simply the amount of dollars allocated for that time period. The rates will simply change according to how much supply is available.

“Remnant” Demand

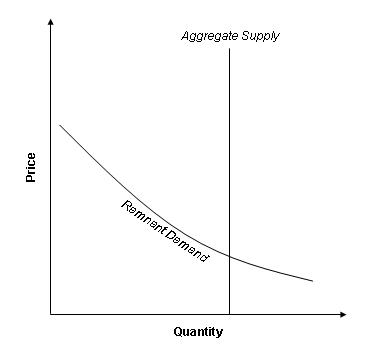

Of course the world really isn’t that simple. Enter remnant demand. I myself have never really like the term remnant but that’s primarily because way too many people pronounce it remAnant. So what is it? I guess people will have their own definitions but I would classify it as anything that hasn’t been reserved at a fixed price. Any CPA or CPC based deal would most likely classify as remnant, as well as any non-guaranteed CPM buys.

Remnant demand is a little more sensible than premium demand — performance will generally matter for these advertisers. This means that there is no longer a ‘fixed’ amount of money flowing into the marketplace, rather, the amount differs depending on the quantity and price at any given point in time. If inventory is cheap an advertiser will buy higher quantities than if the inventory is more expensive. Visually it would look something like this:

The price paid by the publisher would be the intersection of the two curves — OR — if he is successful at some basic Price Discrimination it may be the area under the remnant demand curve (my economics is getting fuzzy). The really interesting question is: what happens when you combine remnant and premium?

The Aggregate Demand Curve

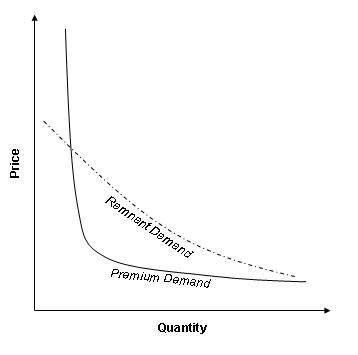

The way to combine the interaction of the premium and remnant demand curves is to think like a publisher. First, lets overlay the two graphs:

Now, lets imagine that all supply is controlled by one publisher and that as this publisher we are guaranteed the $10k in premium demand and now simply have to figure out how to price my inventory to maximize my total revenue. Well, lets think about this. Imagine that the quantity of inventory available in the marketplace sits very close to the left of the graph, a bit to the left of the intersection of the premium and remnant demand curves. At this point the supply curve intersects the two curves where the premium curve is above the remnant curve hence the publisher will allocate all of his inventory to premium demand. This makes a lot of sense right? The premium publisher will pay a higher price which would net the publisher higher revenue.

So here’s the question — what happens when supply lies to the right of this intersection? Well, what would you do if you were the publisher? What I would do is pretty simple. I’d convince premium advertisers that they have to pay more to reserve and allocate a the percentage of my inventory to the left of the intersection to them at a high price — one that’s would generally be higher than the one that remnant advertisers would pay. All other inventory I would sell to remnant advertisers. Ok, so what does this look like? Well simple! We simply vertically add the two curves as follows:

We can simply combine the premium and remnant demand curves to form the aggregate demand curve.

Lets get back to the point

Ok, so that was a whole buncha mumbo jumbo economics. What was the point? We drew some fancy curves and discussed some intersections… so what? Well, we were talking about premium and remnant, specifically why people should stop splitting out the online ad market between the two. Well, how does the above help us? Well first off, from a marketplace perspective it is not difficult to combine premium and remnant. This is my second argument against splitting out the two. When a publisher is trying to maximize revenue, he should be thinking about aggregate demand, not premium and remnant.

Think about some things that might maximize revenue:

- Improve page quality for ad performance

- Attract more and higher quality users

- Increase visitor frequency

- Improve sales efforts

- Improve monetization/optimization tactics

- Leverage behavioral data

How many of these apply solely to premium or remnant? None of them. All of the above are tools that a salesperson can use to grab a bigger piece of the premium pie. All of the above are also things that can help performance advertisers optimize their campaigns. Sure, selling to premium advertisers is different from selling to remnant advertisers, but that can easily be solved by hiring diverse salespeople and focusing them on the right areas. Nowadays most publisher get a significant portion of their revenue from remnant, hence when talking about growth rates in revenue we are really talking about growth in aggregate demand. Here’s the thing — the best techniques for maximizing revenue for publishers are not specific to performance or brand.

So all you fancy wall street analysts — when you’re asking large publishers whether their new focus on behavioral technologies will decrease revenues from premium inventory — stop and think about what you’re saying. There is no such thing as ‘premium inventory’. There is ‘premium demand’, but except for sales no company should make it one of their strategic goals to increase their share of this pool.

Final Thoughts

Before Greg can steel some of my thunder again — part III of this series will be about the growth of remnant and why I expect growth rates in “premium demand’ to slow whereas “remnant demand” will continue to grow drastically. (no it’s not related to social networking). I would also like to mention in the spirit of full disclosure that I know very little about the agency business and most of the statements I made above are based on things I’ve heard from colleagues and friends but not from personal experience.

Also — my economics are definitely fuzzy. I wish I had more time to go and read my old textbooks again, but sadly that isn’t the case. I would greatly appreciate pointers on mistakes I’ve made as I’m sure I’ve oversimplified the problem by quite a bit.

Premium vs. Remnant — (Part I — Supply)

May 10th, 2007

If there is one thing that I have yet to understand about the online advertising business is the insistence in splitting available inventory into two buckets: premium and remnant. Well, I’ve had enough of it. I’m going to lay out my arguments as to why this differentiation is plain silly and I challenge all that use these terms to tell me why in heavens name you should continue to use them. Don’t get me wrong, from a sales perspective it makes sense to split efforts into Agency & Others, (e.g. Premium & Remnant), but from an overall monetization perspective is does not. Yet, when Yahoo held a call with analysts to discuss the Right Media acquisition, multiple “wall street experts” asked questions around “How is this going to impact pricing on remnant?” “Does this mean that Yahoo will focus more on remnant monetization than premium?” (not direct quotes as I couldn’t find a transcript anywhere). Hopefully I can make a good case.

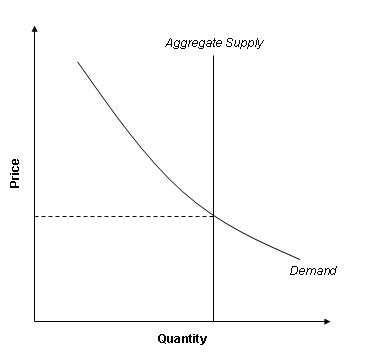

Some Basic Economics of Supply & Demand

Lets start off by discussing some very basic economics — supply & demand. In today’s online advertising marketplace, supply is provided by publishers with ad inventory to sell and demand comes from advertisers and marketers that have dollars to spend. In a traditional supply and demand model suppliers have some flexibility in terms of the amount of goods that they can produce, and buyers will vary the goods they buy based on the market price. E.g., there are very many young kids that would buy an XBox for $10, but Microsoft wouldn’t put very many systems on shelves at that price. So through normal market mechanics some sort of balance price and quantity is found which in generally the intersection of the supply & demand curves. (by the way — if all of this is foreign to you, please go read this wikipedia article). Here’s an example of a traditional supply/demand curve:

Note that these graphs generally refer to the short term. E.g., think of this as a ‘snapshot’ today, or this month. Over the year, Microsoft may change the way they produce Xboxes and this might change the behavior of their entire supply curve. Also, Nintendo might come out with a competing product which pushes the demand curve down.

‘Supply’ in Online Advertising

Now, this simple model doesn’t apply to very much at all as every single product/commodity/industry is slightly different. Online advertising itself is a rather peculiar case, especially on the Supply side of things. First of all, how do we measure supply? Well, most people you ask would probably say “impressions, DUH!“. WRONG. One impression is most definitely not the same as another. A well educated male user with a high income interested in buying a car is worth a heck of a lot more than a 14 year old girl posting on her Myspace page. That’s the thing — the quality of supply changes not only per publisher, but also per user and page. Certain users are worth more… Certain pages are also worth more, not because contextual technology might work, but because the ad might be displayed more prominently, or because this is a page that users tend to stay on for a long time.

Ok, so now what? Well, theoretically we could draw out one individual supply curve for every possible combination of user quality and page, but obviously that’s not very feasible. What we can do is aggregate all of these together into a more theoretical “aggregate supply curve”. Normally aggregate supply is used when observing markets as a whole… which seems fitting here. Now, a normal aggregate supply curve is upward sloping as in the figure above — this is not the case in online advertising.

What’s interesting in online advertising is that publishers do not control the amount of inventory they have. Think about it — you’re the New York Times — is there any way that you could influence the number of visitors to your site TODAY? I guess theoretically you could advertise, but considering this isn’t very cost effective (e.g. a click costs a lot more than the impressions you’d garner), we’ll ignore this case. You could also make the argument that at a certain price the publisher should simply stop serving ads to reduce the overhead in bandwidth and various leasing fees that may come with his adserving solution. The problem is, the publisher won’t know what the price is until after he has sent the impression to his adserver, at which point you might as well serve even the cheapest ad as some money is better than nothing. So what does that mean for our supply & demand curves? Well, rather simple — we simply get a straight line, as follows:

In the graph above, the price for inventory is determined solely by demand. Note that I didn’t draw any separation on the supply side between “premium” and “remnant”. You simply can’t, because there really is no differentiation on supply based on these two factors. One impression on Yahoo! Mail’s login page for a twenty year old male might be premium one second and remnant the next. It’s not dependent on any supply factors, simply on which type of advertiser is buying the inventory. So here comes the first argument against premium & remant — inventory is deemed premium based on the buyer and has absolutely nothing to do at all with the actual ad impression beind sold.

Why is it that we would refer to them differently when the actual inventory is the same? It’s not like we can split the inventory — the same impression can be premium one day and remnant the next. So that’s the first reason why I think the market should stop thinking about “premium vs. remnant”, and instead look at overall supply.

Some Final Thoughts on ‘Supply’

One of the things that I struggled with greatly while writing this post was actually how to model supply. I was hoping to do something fancier than simply place a straight line on my graph. Why is this? Well — as I mentioned above, supply is really a function of user quality, page quality and user timing. For example, the same user on the same page is more valuable the first time he looks at it than the second. How does one forecast this? Intuitively I think people know that the growth rate in supply today is mostly in low quality inventory. Why? Well, people talk about “remnant” inventory growing with sites like Myspace, Youtube and Photobucket. This inventory has very high user frequency, generally low ages and hence is lower quality.

If someone has had some luck actually coming up with a good way to theoretically model a publisher’s supply I would love to hear it. Actually.. just post a comment!

Stay tuned for Part II — We’ll look at demand, and provide more arguments as to why the phrase “premium vs. remnant” should

never again be uttered when discussing the online advertising industry.