Top 5 Media Startup Mistakes

October 7th, 2010

My first title for this post was “top 5 ad-network mistakes”… then I realized that ad-network was a “bad” term… so intead I’m going to refer to a “media startup”. I’ll put networks, DSPs, trade-desks, dynamic creative providers… any company that buys & sells media (*cough* … looks like a network.. *cough*) under this new “media startup” bucket.

It seems every young media startup I talk to keeps making the same mistakes over and over. Well, here goes in no particular order (even though they are numbered #1-#5) my list of things every startup needs to watch out for… maybe I can help prevent someone from making the same mistake!

#1 – Credit / Payment Terms

A $1M insertion order is amazing.

A $1M insertion order where you get paid net-90 but you pay out net-30 can kill your business.

A $1M insertion order where you get paid net-60 but you pay out net-60… can also kill your business.

Here’s the problem. Agency margins have been on a nose dive downwards for years now. One of the ways agencies drive up their profitability by paying everybody late and making a little extra $ on the interest they earn by keeping the money in their bank account. Even if you think the payment terms line up, just one client that sits on their check for too long can be tdetrimental to your business. If you don’t pay your big sellers they cut you off, killing your network. If you push to hard on the agency, they cut you out of next quarter’s budget.

Proper float & credit management is a must for any network. Have an open conversation with agencies and understand when you can realistically expect to be paid, and then make sure there’s always enough cash in the bank to pay sellers and publishers (and employees!). Many a media startup has gone out of business by badly managing their float.

#2 – Boobs

Did you know that perezhilton.com, wwtdd.com and idontlikeyouinthatway.com are present in some shape or form on every single exchange and supply platform from the aggregators (PubMatic, Rubicon, Admeld, OpenX, etc.) to the big guys (Right Media, Google)? These “Entertainment” sites make liberal usage of pictures of scantily clad celebrities, their sexcapades and lots of other inappropriate content.

Now on a normal remarketing campaign the performance might be great, but there’s nothing worse than an angry email from your advertiser because your ads just showed up next to this page.

In the best case your reputation just took a little hit. In the worst case your advertisers simply refuse to pay out multi-hundred thousand dollar budget amounts…. ouch.

It’s imperative that a network or buying desk has a strategy in place for managing inappropriate and sensitive content. Don’t assume that the “Entertainment” channel is fun sites that you can run any advertiser on… you’ll be in serious trouble if you do. On RTB you obviously get the URL, so use it. Supply platforms also have various forms of brand protection… Advertising online is kind of like teenage sex… first take a sex-ed class to learn what the forms of protection are … and then don’t forget to use protection in practice!

#3 – Malvertisements

Here’s a very common story. One of your sales guys comes in super excited… he just closed an *amazing* deal. $0.75 CPM, no goals, all european countries for a major brand-name advertiser with a huge $100k budget. To top it off, the buyer will pre-pay $50k up front and promises net-15 payment terms.

The deal goes live… and within 24-hours exchanges shut you down and all of your publishers turn off their tags because for some strange reason all of their visitors are complaining that you are trying to install some sort of trojan/malware program with your ads

Yep, there’s bad guys out there that will pay you serious cash to run ads that are really viruses in disguise. When you load them from the office they behave. Enter night-time and they turn into nasty beasts that will cost you publisher relationships, a bad rap with Sandi and potential scrutiny from the feds.

General rule of thumb… if the deal is too good to be true, it probably is. Google has done a terrific job setting up a website to educate the industry about this on www.anti-malvertising.com. Make sure every single one of your sales & ops staff reads this entire site in detail.

#4 – Not Focusing on Sales

If you are building something that’s amazing & scientific, it’s probably the wrong thing to build. No seriously… If you have even one PhD on staff you’re probably doing something wrong.

Quarter after quarter at Right Media I’d work with a team of engineers to push out improvements & features to the optimization system to increase efficiency, ROI & spend. You’d think that in a business running several billion ads a day that this would be the single largest driver of company revenue. Yet… one sales guy at the original Right Media “Remix” Ad-Network single-handedly blew me out of the water one quarter with a single insertion order… and the deal didn’t even use optimization.

Relationships matter… a lot. Not every buyer out there just wants to buy into a magic black box that will auto-magically uber-optimize their life. Advertising is, believe it or not, about more than just clicks & conversions. There’s an inherent understanding of the target audience and the media and buyers want to work with companies that understand how they are thinking and who they are looking for. This means that the buyer wants to talk to someone he can relate to, who listens to him and who he can trust.

This is why every media startup needs a strong sales team. You might have the greatest technology in the world, but if you can’t sell it, it’s not going to get you far. The smart guy in the room? They’re the ones that hire the sales guy that will close the multi-million $ deal. [The above mentioned sales guy went to work for Invite Media, now of course a Google company...]

#5 – Over building technology

To some extent this is a follow-up on the previous point, but so many companies I talk to seriously over-build their technology. The market today is simple. Yes, we will definitely be in a world one day with “traders” sitting at terminals with tickers and fancy secondary future markets and involvement from some of Wall St’s finest…. just not today.

Today, one great trafficker/optimization analyst can beat almost any algorithm out there A team of 5 temps working for a week can apply categorizations to the top 1000 internet sites with similar accuracy to the fanciest semantic engine. A smart BD guy can buy KBB data w/out a deep API integration to a data exchange. A buying strategy of “remarketing” will out-perform any other campaign strategy or behavioral data by at least 10x.

Now don’t get me wrong… there is definitely a market for technology and technology is the only way in which you take the behaviors of brilliant individuals and scale them to be a hundred million $ business. Here’s the problem, most companies start by building technology, then trying to apply it. If you want to be a successful media business you should do the opposite. Hire some great people, watch how they operate, then build technology to automate what they do.

Conclusion…

The above 5 are common mistakes… but there’s one very simple rule of thumb any and every CEO, investor or board member can use to judge the quality of a media startup.

If you ain’t making money, you ain’t doing it right.

Seriously. More than 3 months old with 0 revenue? Likely to fail. Low revenue with high burn? Doomed to fail. The simple answer is it’s easy to get at least one agency to buy in as an early adopter and throw you some $ to “test”. If you can’t do this, you’re doing something wrong!

PS: Shameless self-promotional use of the blog here but… AppNexus is HIRING!!

Price floors, second price auctions and market dynamics

September 25th, 2010

One of the things that is often discussed but not often written about are the market mechanics that surround the new RTB enabled exchanges & SSPs. From a design perspective most marketplaces these days have adopted some modified form of a second-price auction. The winner of the ad impression pays the seller not his actual bid, but the second highest bid.

Second price theory works as follows: Imagine that I’m selling a Monet painting. There are people that want to buy it and each has a maximum price he’s willing to pay but of course doesn’t want to pay a penny more than he has to to get the actual painting. If I tell my buyers that they’ll only pay the second highest price then each can safely give me their maximum price because they know they’ll only pay the amount they need to to beat the next highest guy. That sounds nice right? Second price auctions maximize revenue and make everyone’s life easier and create simple and efficient markets.

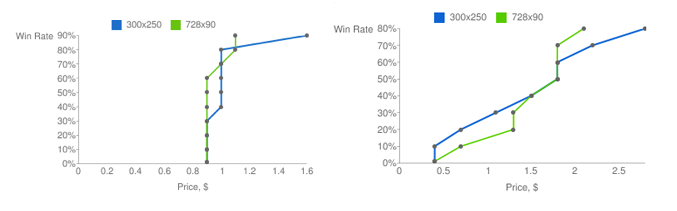

The problem is, reality doesn’t seem to quite follow the theory when we look at advertising today. Take a look at the below yield curves for two publishers coming in from two different exchanges. Both of these exchanges use a second price auction model.

The way the yield curves are read is pretty simple. On the X-axis you have a CPM bid-price and on the Y-axis you have the % winrate — the probability that you will win an impression from this publisher for this ad-size if you bid this price. On the right we see a relatively logical and predictable curve — you can’t win much below $0.40, at $0.50 you win about 10% of the time and above $2.00 you will win about 70% of the time. The higher the price point, the less demand and hence the higher the winrate.

On the left you see a rather curious pattern, below $0.90 one wins nothing whereas at $1.00 you get 80-90% of all impressions. Obviously not an efficient market. In this case, the publisher has set a price floor of about $0.90 for the inventory.

This is pretty common these days in RTB — publishers are absolutely terrified about cannibalizing their rate card and are hence forcing a “premium” for RTB buyers. This is a particularly interesting case because if you look at the actual win-rates it’s pretty obvious that there is barely any demand above their actual floor… or in other words, it just ain’t worth that much. So why would a publisher set a floor and sacrifice their revenues?

What the publishers are afraid of

Fundamentally publishers are afraid that advertisers will “game” their auctions and the net result will be lower effective CPMs.

Let’s take a completely theoretical auction on Google AdExchange for a 29 year old male user seeing his third ad on a specific page about ford pickup trucks on CNN.com who has been identified as an in market cell phone shopper. Four buyers are interested in this specific impression…

- Ford buying the keywords “pickup trucks” — values the impression at a $5.00 eCPM (derived from a CPC price)

- AT&T targeting in market cell phone buyers using third party data at a $3.00 CPM

- A branded Kraft campaign that is trying to reach 29 year old males at a $2.00 CPM

In second price theory each would submit this price, Ford would win the impression with it’s $5.00 bid and pay $3.00 to match AT&T’s second price.

Here’s the problem… frequency & an abundance of supply. Users see multiple ads. Frequency is also by far the most significant variable for optimizing response to ads. Hence each buyer is only interested in hitting this user a limited number of times with their ads.

For the sake of argument, let’s assume that our 29 year old Male, Joe, is browsing a number of different articles on CNN.com and there are 10 different opportunities to deliver an ad to him. Let’s also assume that our buyers continue to bid on each and every impression. To model frequency let’s assume that after each impression delivered the advertiser will bid half as much for each subsequent impression. Under these assumptions here’s how the bids would pan out over a number of auctions:

| Auction | Ford | AT&T | Kraft | Price paid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | 5.00 | 3.00 | $2.00 | $3.00 |

| #2 | $2.50 | $3.00 | $2.00 | $2.50 |

| #3 | $2.50 | $1.25 | $2.00 | $2.00 |

| #4 | $1.25 | $1.25 | $2.00 | $1.25 |

| #5 | $1.25 | $1.25 | $1.00 | $1.25 |

| #6 | $0.63 | $1.25 | $1.00 | $1.00 |

| #7 | $0.63 | $0.63 | $1.00 | $0.63 |

| #8 | $0.63 | $0.63 | $0.50 | $0.63 |

| #9 | $0.31 | $0.63 | $0.50 | $0.50 |

| #10 | $0.31 | $0.31 | $0.50 | $0.31 |

What we see is that for each auction the publisher’s revenue is maximized with CPMs starting at $2.50 but then very quickly dropping down to $0.63 cents.

Now here’s where theory and practice start to separate. In the above scenario, Ford pays an average of $1.72 CPM to show this user four ads. This is quite a bit higher than the average CPM and Ford decides to try a new bidding strategy to try to reduce his cost. Rather than always putting out his maximum value to the ad exchange he holds back a little bit and decides not to bid until the 6th impression.

Here’s what happens:

| Auction | Ford | AT&T | Kraft | Price Paid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | no bid | $3.00 | $2.00 | $2.00 |

| #2 | no bid | $1.50 | $2.00 | $1.50 |

| #3 | no bid | $1.25 | $1.00 | $1.00 |

| #4 | no bid | $0.63 | $0.50 | $0.63 |

| #5 | no bid | $0.33 | $0.50 | $0.33 |

| #6 | $3.00 | $0.33 | $0.25 | $0.33 |

| #7 | $1.50 | $0.33 | $0.25 | $0.33 |

| #8 | $0.75 | $0.33 | $0.25 | $0.33 |

| #9 | $0.38 | $0.33 | $0.25 | $0.33 |

| #10 | $0.19 | $0.33 | $0.25 | $0.25 |

What you see in the above is that Ford now buys four impressions, slightly further down in the users session but for an average CPM of $0.33… 81% cheaper than were he just to submit a bid on each and every impression.

Of course this is a hypothetical situation, but it does show a point — if demand is limited then for buyers a very simple bidding strategy can have a large impact on cost and greatly increase ROI.

Let’s now imagine that the publisher realizes the advertisers are doing this and sets an artificially high floor price to try to protect his margins — $1.50. Instead of accepting a paying ad he will show a simple house ad instead.

Here’s now what the auction looks like:

| Auction | Ford | AT&T | Kraft | Price Paid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | no bid | $3.00 | $2.00 | $2.00 |

| #2 | no bid | $1.50 | $2.00 | $1.50 |

| #3 | no bid | $1.25 | $1.00 | psa |

| #4 | no bid | $0.63 | $0.50 | psa |

| #5 | no bid | $0.33 | $0.50 | psa |

| #6 | $3.00 | $0.33 | $0.25 | $1.50 |

| #7 | $1.50 | $0.33 | $0.25 | $1.50 |

| #8 | $0.75 | $0.33 | $0.25 | psa |

| #9 | $0.38 | $0.33 | $0.25 | psa |

| #10 | $0.19 | $0.33 | $0.25 | psa |

The publisher has certainly succeeded in driving up the average Ford CPM — back up to $1.50 from the earlier $0.33. CPMs are down to $0.65 but the overall average is actually *down* from $0.71 CPM.

Here we see how the artificially high price actually ends up driving overall revenue down by limiting the number of impressions sold significantly.

Of course those of you paying attention would point out that a lower floor could potentially increase revenue over the no floor situation!

So what gives?

Direct marketers have known the above for years. This is why very few pure response driven buyers pay rate-card for the ESPN home page. What scares publishers is the idea that branded buyers could start doing the same thing. The knee-jerk reaction in this case is to set arbitrarily high floor prices on marketplace inventory to try to protect the channel conflict.

Floor prices themselves aren’t necessarily that bad. In fact, there are good reasons for setting them. First, there are brand buyers that are paying rate card for guaranteed inventory — there is no reason to expose that same inventory to those buyers on a marketplace for a much lower rate. In other cases, a publisher might just be better off displaying internal house ads rather than showing a crappy blinky offer that annoys visitors at a low CPM.

For example, imagine you’re ESPN and you have a new “Videos” section where you just started running pre-roll ads $30 CPM. If ESPN were to show the crappy blinky offer (not that they have the demand problem), they’d make $0.10 for a thousand impressions and probably risk losing a small percentage of their audience in the process. On the other hand, a benign house ad announcing the new “Videos” section of the site would both increase site-traffic and visitor loyalty, but actually generate revenue. If they get 5 clicks per thousand impressions on the house ads they’ll actually be able to net out $0.15 in advertising revenue from the 5 pre-roll impressions served on the video site (and even more if users watch more than one video).

Going back to market mechanics

Let’s go back to Market mechanics for a second. Today what we need to avoid are knee-jerk set crazy high floor prices — a floor price that is too high will simply result in lower RPMs for the publisher. Publishers must understand that there is a significant pool of demand, specifically the ROI & response driven side, that simply won’t buy the inventory for rate-card prices.

In the end it comes down to information and controls. Publishers need to understand the market mechanics and the yield that they can derive from their inventory. At the moment I’m not aware of any major marketplace providers that supply this type of information.

I have a lot of thoughts on the tools and controls a pub should have and also on how one might change market mechanics away from a true 2nd price auction to efficiently deal with this — but I think this post is getting long enough… I’ll save that for the next one (which hopefully won’t be 5 months in the making!)

I don’t care who you say you are, what do you DO?

May 3rd, 2009

One of the things that boggles my mind is how massively fragmented and confusing the display world still is. It’s been over three years since the first ad-exchange launched yet the world hasn’t significantly changed. What makes matters more confusing is that there is no consistent terminology to describe what a company does. It seems everybody describes themselves as either a platform, marketplace or exchange — so what’s the difference?

A company can call itself a publisher, an agency, a network, a broker, a marketplace, an exchange, an optimizer — what does it all mean? What’s the difference between Right Media and Contextweb? Admeld and Rubicon? That’s really the problem — today’s commonly used labels are useless.

Instead of evaluating a company based on labels, evaluate it based on the services it provides, technology it has, the partners it works with, the revenue model and the media revenue it facilitates. Note — below I focus entirely on companies that in some shape or form touch an *impression* — either as a technology provider, buyer or seller. There are peripheral companies that provide a whole world of supporting services, but I’m leaving those out for now to avoid confusion.

Services

Each company provides certain core services to partners, customers and vendors. These primarily center around the relationship the company has with the media that flows through it.

| Service | Description | Example | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selling of Owned & Operated Media | The company represents and sells media inventory that it owns. | Yahoo selling inventory on Yahoo Mail. New York Times selling it’s inventory |

Company’s sole objective is to maximize CPMs and revenue. |

| Arbitrage of Off-Network Media | The company resells media inventory that it acquires from other services. | Yahoo selling users on the newspaper consortium. Rubicon selling inventory from it’s network of publishers. |

Company takes arbitrage of the inventory which means that it’s incentivized to buy low and sell high to maximize it’s own revenue rather than that of the inventory owner or the advertiser. |

| Inventory or Advertiser Representation Services | The company helps inventory owners sell inventory at a fixed margin. | AdMeld serving as a direct rep for publishers remant X+1 managing all campaigns for a specific advertiser or agency |

Company is incentivized to maximize revenue for the inventory owner or ROI for the advertiser. |

| Data Aggregation | Company aggregates user data and resells it | BlueKai’s data exchange Exelate’s data marketplace |

Company hates Safari and IE8 |

Technologies

There are certain core technologies that define what a company does. Note that you will find technologies such as dynamic creative optimization, behavioral classification and contextualization missing from the below list as they are differentiators — they don’t define what a company does but provide a competitive advantage over the competition.

| Technology | Description | Example | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internally available adserver | Company has a proprietary in-house adserving system. | Specific Media has it’s own proprietary adserving technology that it uses to manage it’s network. | Company sees technology as a competitive asset against competitors. |

| Externally available adserver | An adserver that the company licenses (either free or paid) to third party companies to manage their own online media. | OpenX providing their hosted adserver to publishers Invite Media’s cross-exchange Bid Manager platform Google’s Ad Manager |

Multiple companies using the same platform provides both aggregation and consolidation opportunities. Technology in this case helps build an open platform (since everyone has access). |

| Internal Trading | Inventory run through the externally available adserver can be bought and sold internally | Google’s AdEx allows multiple participants to use the externally available adserver to buy and sell media. Right Media’s NMX customers can buy and sell media to each-other directly. |

There is a network effect related to the size of the platform. The more participants the more value there is for everybody involved. |

| Buying APIs | Company provides an API, either real-time or non, through which buyers can upload creatives and manage campaigns. | Right Media allows it’s customers to traffic line items and creatives using it’s APIs. | Company is empowering buyers to be smarter by enabling deeper integration across platforms. The stronger the APIs, the more the buyers can spend. |

| Selling API | Company provides a real-time API through which sellers can ask in real-time how much company is willing to pay for an impression. | Right Media and Advertising.com respond in real-time to a ‘get-price’ request from Fox Interactive Media’s auction technology | Company can value inventory in real-time. |

Size Matters

Last but not least, the size and the partnerships of a company matters. I’ve written before about the perils of building technology in a void. You can have the most amazing platform that provides great services, but if you’re only running a few thousand dollars a month it’s all moot in the grand scheme of things.

Size can be measured either in impressions or revenue, the latter being far more telling. Getting a billion impressions of traffic a day isn’t hard these days — between Facebook and Myspace alone you probably have close to fifteen billion impressions of traffic running daily.

There’s a huge difference between a partnership and a media relationship. If you’re willing to foot the minimum monthly bill, anybody can buy Yahoo’s inventory through the Right Media platform. That doesn’t say much about who you are as a company. A partnership is different — it might be deep API integrations tying two platforms together or co-selling and marketing a joint solution.

What does it all mean?

Phew… that was a long list, so what does it all mean? Well, the above provides a slightly less fuzzy framework than the classical “ad-network”, “marketplace” or “exchange” commonly used labels to describe a company. Let’s look at a few examples:

Rubicon Project provides publisher representation services through it’s network optimization platform, arbitrages inventory through it’s internal sales team has both an internal and has an externally available adserver (one for the sales team and one for publishers) and is rumored to be working on real time buying APIs. That’s a hell of a lot more descriptive than “publisher aggregator” or “network optimizer”. The one thing I always find confusing about rubicon is that it their incentives seem to be fundamentally misaligned. How can you both arbitrage inventory and serve as a publisher representative? Updated (5/3/09 @ 8pm EST) — I seem to be misinformed. Per comments, Rubicon does not sell inventory directly to agencies.

Compare this to AdMeld which provides publisher representation services through it’s network optimization platform — an externally available adserver — and provides buying APIs (currently via passback). So what’s the difference with Rubicon? Well, one has an internal ad-network and the other doesn’t — different incentives. Publishers are starting to treat Rubicon as another ad-network in the daisy chain whereas AdMeld sells all remnant inventory as a trusted partner.

ContextWeb has an internal adserver (with a self-service interface… I don’t count that as external), they arbitrage inventory, and provide buying APIs. Compare this to Right Media which has an externally available adserver, buying and selling APIs, internal trading, data aggregation and arbitrages media (through BlueLithium/Yahoo Network). Both are “exchanges”, but clearly there is a pretty big difference between the two!

Of course if you get to Google your mind starts to explode just a little bit — as they do everything. Seriously. They buy & sell, have multiple adservers, provide buying APIs, internal trading, data aggregation…

Final Thoughts

I hope this post has given you some ways to start thinking about companies in the online ad space. I’d love to hear your feedback in the comments — what core services & technologies am I missing?

Now — next time someone says — “I’m an exchange”, why not ask — “Ok, that’s great, but what do you really do.”

Are you optimizing on the ‘View’?

December 22nd, 2008

If you haven’t already, you must read this post by Fred Wilson which summarizes a recent Comscore whitepaper Whiter The Click?.

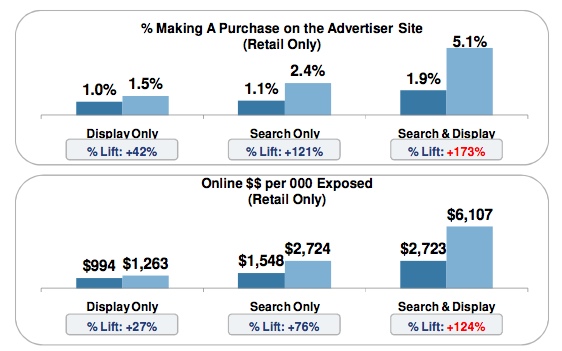

I’m not going to re-summarize the paper as Fred’s post already does that. The findings are clear — display has a significant impact on consumers which is often not shown by clicks alone. Check out the graph:

This means that if you aren’t tracking (and billing!) on this behavior on performance based campaigns you are leaving some serious money on the table!

Question of the day — who’s got a good technology to track this?

The Dangers of Negative Context — McCain Recap

July 30th, 2008

This is a fairly well known problem in the industry — you target a keyword, say ‘travel’, thinking that you will end up on searches & sites relating to travel. Next thing you know you end up next to a New York Times article talking about the recent plane crash in Lima and how it’s limiting travel to South America — oops

Well — the same thing happened to my blog today and good old Mr. John McCain. Although I guess it shouldn’t be too surprising, I found it slightly ironic that John McCain was advertising next my blog post criticizing his advertisements. See the bottom left on the following screenshot:

And the landing page:

Now first off — these ads look much better than before — maybe they read my earlier post? Now I am incredibly curious whether or not these ads are ROI positive in that they bring in more money in donations than is being spent on media. Anybody know??

John McCain ads look like crappy giveaway offers

July 20th, 2008

Saw this John McCain ad on a random blog this evening:

Reminds me greatly of the giveaways you normally see on myspace… seems they forgot to leave out the “get a free lecture on public policy!!”.

Landing pages even look the same — a simple form with a ZIP & email. I wonder if they’ll sell my email address for $2.00 and use my Zip for later retargeting later.

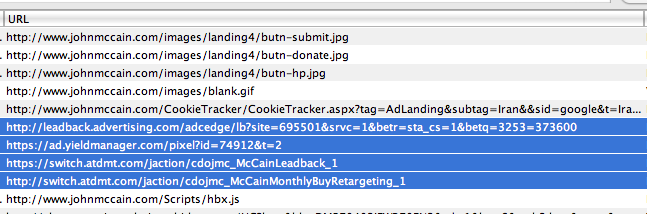

What’s interesting though is that it looks like the McCain campaign is doing some serious remarketing on “clickers”. There are pixels there for the Right Media Exchange, Ad.com’s Leadback and Atlas!

Is Google taking behavioral data to display?

July 18th, 2008

I was just browsing on my gender test blog post and noticed the following ad:

So normally you’d say — so what mike, it’s just an ad for senseo! Well this ad is special because I was just searching for Senseo coffee pods earlyt his morning (both via Google & Amazon.com). I find it highly unlikely that this is a pure coincidence. Here’s the clickstream (broken into multiple lines and shortened for legibility):

http://pagead2.googlesyndication.com/pagead/adclick?sa=L&ai=BSrzSV[...] http://www.sharesenseo.com/index.jsp?q=a-googlewomen

Funny that there is a nice “q=a-googlewomen” inserted into the landing page — I swear the gender test showed me to be a man!! So this is all purely speculative of course, but if this is indeed true then we suddenly have the world’s best behavioral display network to compete with.

Are you generating revenue?

July 1st, 2008

A few weeks ago I wrote a post about the difficult times that tech startups are having in the industry today. Reading through the post, I realized there was a key point that I forgot to make. Whether or not your company is a services business, a technology play or a media company:

If you aren’t generating revenue, it’s time to re-evaluate your business.

There is so much VC money out there these days (although word on the street is it’s drying up!), that it’s easy to forgo initial revenue and start building & scaling a business in a void without having hard cash paying customers. Here’s the thing — you should be able to prove your technology quickly and with minimal investment… if you can’t, you’re overthinking either your product or overestimating the requirements of your clients. In fact, with the right contacts you can probably sell a 20-line PHP script as a “pixel server” — at least to a network or agency that desperately needs to have “behavioral technology” for the next big agency deal.

Of course the script won’t scale, and it probably won’t work as a standalone product for multiple customers which means you’ll have to rewrite it and hire some real engineering talent to turn it into a packageable product. But if you have an idea — build a POC quickly, get yourself a customer, prove there’s interest and start generating revenue! Doesn’t matter if it’s adserver, behavioral tracking, a new media network — each idea has a revenue-generating “quick win” you can close to prove the business works. Right Media was a profitable for over a year before it launched the exchange. A single good CPA deal with AOL funded most of the first year of the company!

And it’s not just about the revenue. Real customers provide real data, real feedback and real stats about scalability & performance — invaluable feedback & information that will help you build a better and ultimately more competitive final product and/or service offering.

I’m not saying you have to be profitable (although if you’re a pure media company you better have a damn good reason not to be). There is definitely an argument to be made that investing in engineering today will pay off in revenues later, but that does not give you an excuse to develop in a void hoping that your product will be a smash hit.

If you’re not making money now, chances are you won’t make any later either.

A Nice Online-Ad 101 Post

June 4th, 2008

I stumbled across an interesting post written by Ian Thomas from Microsoft — Online Advertising Business 101, Part I – The Online Advertising Value Chain. It’s a great basic read for anyone who wants to start with the basics of who does what in our industry.

I will point out that Ian is clearly on the tech side of the fence though — he draws the industry as a flow of impressions from publishers to advertisers, whereas most media focused folks will think of the reverse — money flowing from the advertiser to the publisher. If you have no clue what I”m talking about, check out my old post: Business or Tech.

The Facebook API revolution

September 25th, 2007

No, this isn’t another “OMG, the facebook API IS AWESOME” post. I mean, it is, it’s pretty damn cool, I’ve played with it a bit this month. The real revolution with the facebook API are the server-side requests.

Traditionally widgets & plugins interfaced with social networks by placing snippets of HTML on profile pages. In the Facebook world no content can show up on a user’s profile without passing through Facebook’s servers first. Even your actual application pages must either be within an IFRAME or pass through Facebook. This process provides Facebook with an extraordinary level of control over what can and cannot be displayed on a user’s page. FB can perform a virus scan on all content and analyze any scripts for vulnerabilities or exploits. By directly serving content Facebook also eliminates cookie access — making it far more difficult to track or distribute data about their users.

Yet, the approach has it’s limitations for application developers. I tried briefly to build a “stalker tracker” application which using cookies would tell the user how many people regularly checkout their profile page. No matter what I tried, I couldn’t get access to the cookie without somehow initiating a click — rendering my application completely useless.

Why should you care? Well — advertising isn’t that much different from a traditional social networking widget — both are delivered via a snippet of HTML. Online ads have also been plagued by security issues this past year and I wouldn’t be surprised if the bigger players (Myspace, Yahoo, MSN, etc.) start to ask for server-side ad-requests soon. Server-side requests are the only way that a seller can technically guarantee the safety of third-party ads. Of course this will open up a world of technical challenges — server-side cookies storage, strict global latency requirements and a need for increased capacity to only name a few.