Price floors, second price auctions and market dynamics

September 25th, 2010

One of the things that is often discussed but not often written about are the market mechanics that surround the new RTB enabled exchanges & SSPs. From a design perspective most marketplaces these days have adopted some modified form of a second-price auction. The winner of the ad impression pays the seller not his actual bid, but the second highest bid.

Second price theory works as follows: Imagine that I’m selling a Monet painting. There are people that want to buy it and each has a maximum price he’s willing to pay but of course doesn’t want to pay a penny more than he has to to get the actual painting. If I tell my buyers that they’ll only pay the second highest price then each can safely give me their maximum price because they know they’ll only pay the amount they need to to beat the next highest guy. That sounds nice right? Second price auctions maximize revenue and make everyone’s life easier and create simple and efficient markets.

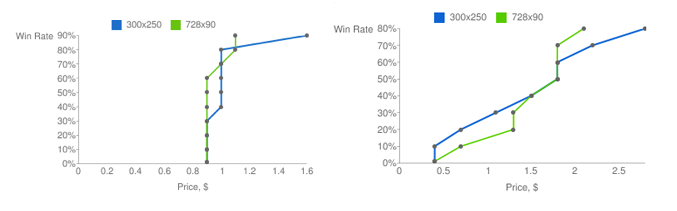

The problem is, reality doesn’t seem to quite follow the theory when we look at advertising today. Take a look at the below yield curves for two publishers coming in from two different exchanges. Both of these exchanges use a second price auction model.

The way the yield curves are read is pretty simple. On the X-axis you have a CPM bid-price and on the Y-axis you have the % winrate — the probability that you will win an impression from this publisher for this ad-size if you bid this price. On the right we see a relatively logical and predictable curve — you can’t win much below $0.40, at $0.50 you win about 10% of the time and above $2.00 you will win about 70% of the time. The higher the price point, the less demand and hence the higher the winrate.

On the left you see a rather curious pattern, below $0.90 one wins nothing whereas at $1.00 you get 80-90% of all impressions. Obviously not an efficient market. In this case, the publisher has set a price floor of about $0.90 for the inventory.

This is pretty common these days in RTB — publishers are absolutely terrified about cannibalizing their rate card and are hence forcing a “premium” for RTB buyers. This is a particularly interesting case because if you look at the actual win-rates it’s pretty obvious that there is barely any demand above their actual floor… or in other words, it just ain’t worth that much. So why would a publisher set a floor and sacrifice their revenues?

What the publishers are afraid of

Fundamentally publishers are afraid that advertisers will “game” their auctions and the net result will be lower effective CPMs.

Let’s take a completely theoretical auction on Google AdExchange for a 29 year old male user seeing his third ad on a specific page about ford pickup trucks on CNN.com who has been identified as an in market cell phone shopper. Four buyers are interested in this specific impression…

- Ford buying the keywords “pickup trucks” — values the impression at a $5.00 eCPM (derived from a CPC price)

- AT&T targeting in market cell phone buyers using third party data at a $3.00 CPM

- A branded Kraft campaign that is trying to reach 29 year old males at a $2.00 CPM

In second price theory each would submit this price, Ford would win the impression with it’s $5.00 bid and pay $3.00 to match AT&T’s second price.

Here’s the problem… frequency & an abundance of supply. Users see multiple ads. Frequency is also by far the most significant variable for optimizing response to ads. Hence each buyer is only interested in hitting this user a limited number of times with their ads.

For the sake of argument, let’s assume that our 29 year old Male, Joe, is browsing a number of different articles on CNN.com and there are 10 different opportunities to deliver an ad to him. Let’s also assume that our buyers continue to bid on each and every impression. To model frequency let’s assume that after each impression delivered the advertiser will bid half as much for each subsequent impression. Under these assumptions here’s how the bids would pan out over a number of auctions:

| Auction | Ford | AT&T | Kraft | Price paid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | 5.00 | 3.00 | $2.00 | $3.00 |

| #2 | $2.50 | $3.00 | $2.00 | $2.50 |

| #3 | $2.50 | $1.25 | $2.00 | $2.00 |

| #4 | $1.25 | $1.25 | $2.00 | $1.25 |

| #5 | $1.25 | $1.25 | $1.00 | $1.25 |

| #6 | $0.63 | $1.25 | $1.00 | $1.00 |

| #7 | $0.63 | $0.63 | $1.00 | $0.63 |

| #8 | $0.63 | $0.63 | $0.50 | $0.63 |

| #9 | $0.31 | $0.63 | $0.50 | $0.50 |

| #10 | $0.31 | $0.31 | $0.50 | $0.31 |

What we see is that for each auction the publisher’s revenue is maximized with CPMs starting at $2.50 but then very quickly dropping down to $0.63 cents.

Now here’s where theory and practice start to separate. In the above scenario, Ford pays an average of $1.72 CPM to show this user four ads. This is quite a bit higher than the average CPM and Ford decides to try a new bidding strategy to try to reduce his cost. Rather than always putting out his maximum value to the ad exchange he holds back a little bit and decides not to bid until the 6th impression.

Here’s what happens:

| Auction | Ford | AT&T | Kraft | Price Paid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | no bid | $3.00 | $2.00 | $2.00 |

| #2 | no bid | $1.50 | $2.00 | $1.50 |

| #3 | no bid | $1.25 | $1.00 | $1.00 |

| #4 | no bid | $0.63 | $0.50 | $0.63 |

| #5 | no bid | $0.33 | $0.50 | $0.33 |

| #6 | $3.00 | $0.33 | $0.25 | $0.33 |

| #7 | $1.50 | $0.33 | $0.25 | $0.33 |

| #8 | $0.75 | $0.33 | $0.25 | $0.33 |

| #9 | $0.38 | $0.33 | $0.25 | $0.33 |

| #10 | $0.19 | $0.33 | $0.25 | $0.25 |

What you see in the above is that Ford now buys four impressions, slightly further down in the users session but for an average CPM of $0.33… 81% cheaper than were he just to submit a bid on each and every impression.

Of course this is a hypothetical situation, but it does show a point — if demand is limited then for buyers a very simple bidding strategy can have a large impact on cost and greatly increase ROI.

Let’s now imagine that the publisher realizes the advertisers are doing this and sets an artificially high floor price to try to protect his margins — $1.50. Instead of accepting a paying ad he will show a simple house ad instead.

Here’s now what the auction looks like:

| Auction | Ford | AT&T | Kraft | Price Paid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | no bid | $3.00 | $2.00 | $2.00 |

| #2 | no bid | $1.50 | $2.00 | $1.50 |

| #3 | no bid | $1.25 | $1.00 | psa |

| #4 | no bid | $0.63 | $0.50 | psa |

| #5 | no bid | $0.33 | $0.50 | psa |

| #6 | $3.00 | $0.33 | $0.25 | $1.50 |

| #7 | $1.50 | $0.33 | $0.25 | $1.50 |

| #8 | $0.75 | $0.33 | $0.25 | psa |

| #9 | $0.38 | $0.33 | $0.25 | psa |

| #10 | $0.19 | $0.33 | $0.25 | psa |

The publisher has certainly succeeded in driving up the average Ford CPM — back up to $1.50 from the earlier $0.33. CPMs are down to $0.65 but the overall average is actually *down* from $0.71 CPM.

Here we see how the artificially high price actually ends up driving overall revenue down by limiting the number of impressions sold significantly.

Of course those of you paying attention would point out that a lower floor could potentially increase revenue over the no floor situation!

So what gives?

Direct marketers have known the above for years. This is why very few pure response driven buyers pay rate-card for the ESPN home page. What scares publishers is the idea that branded buyers could start doing the same thing. The knee-jerk reaction in this case is to set arbitrarily high floor prices on marketplace inventory to try to protect the channel conflict.

Floor prices themselves aren’t necessarily that bad. In fact, there are good reasons for setting them. First, there are brand buyers that are paying rate card for guaranteed inventory — there is no reason to expose that same inventory to those buyers on a marketplace for a much lower rate. In other cases, a publisher might just be better off displaying internal house ads rather than showing a crappy blinky offer that annoys visitors at a low CPM.

For example, imagine you’re ESPN and you have a new “Videos” section where you just started running pre-roll ads $30 CPM. If ESPN were to show the crappy blinky offer (not that they have the demand problem), they’d make $0.10 for a thousand impressions and probably risk losing a small percentage of their audience in the process. On the other hand, a benign house ad announcing the new “Videos” section of the site would both increase site-traffic and visitor loyalty, but actually generate revenue. If they get 5 clicks per thousand impressions on the house ads they’ll actually be able to net out $0.15 in advertising revenue from the 5 pre-roll impressions served on the video site (and even more if users watch more than one video).

Going back to market mechanics

Let’s go back to Market mechanics for a second. Today what we need to avoid are knee-jerk set crazy high floor prices — a floor price that is too high will simply result in lower RPMs for the publisher. Publishers must understand that there is a significant pool of demand, specifically the ROI & response driven side, that simply won’t buy the inventory for rate-card prices.

In the end it comes down to information and controls. Publishers need to understand the market mechanics and the yield that they can derive from their inventory. At the moment I’m not aware of any major marketplace providers that supply this type of information.

I have a lot of thoughts on the tools and controls a pub should have and also on how one might change market mechanics away from a true 2nd price auction to efficiently deal with this — but I think this post is getting long enough… I’ll save that for the next one (which hopefully won’t be 5 months in the making!)

Related Posts:

- Premium vs. Remnant — (Part I — Supply)

- Premium vs. Remnant — (Part II — Demand)

- Premium vs. Remnant — (Part III — Remnant)

- The Ad-Exchange Model (Part II)

- Microsoft/ 24-7 Real Media Rumors

-

http://www.sociocast.com Albert Azout

-

Matthieu

-

Mike

-

http://www.cogmap.com/blog/ Brent

-

Mike

-

Dino

-

Mike

-

Dino

-

http://Forbes.com Achir

-

http://www.acceleration.biz Clive

-

Emily

-

ian

-

http://www.viraladnetwork.net/blog/author/Tim%20Wintle/ Tim Wintle

-

http://www.ciblage-comportemental.net/blog/2010/09/25/price-floors-second-price-auctions-and-market-dynamics/ Behavioral Advertising / Publicité Comportementale » Price floors, second price auctions and market dynamics

-

Ilya Kipnis

-

http://www2.recoset.com/content/2012/02/peeking-into-the-black-box-part-2-algorithm-meets-world/ Peeking Into the Black Box, Part 2: Algorithm Meets World | Recoset Machine Learning and Predictive Analytics

-

http://www.zip-repair.org/ free zip repair

-

http://www.key-logger.ws/ keylogger

-

sachin ruhela

-

http://www.keystrokecapture.ws/ keylogger

-

Hardwood Orang