Premium vs. Remnant — (Part I — Supply)

May 10th, 2007

If there is one thing that I have yet to understand about the online advertising business is the insistence in splitting available inventory into two buckets: premium and remnant. Well, I’ve had enough of it. I’m going to lay out my arguments as to why this differentiation is plain silly and I challenge all that use these terms to tell me why in heavens name you should continue to use them. Don’t get me wrong, from a sales perspective it makes sense to split efforts into Agency & Others, (e.g. Premium & Remnant), but from an overall monetization perspective is does not. Yet, when Yahoo held a call with analysts to discuss the Right Media acquisition, multiple “wall street experts” asked questions around “How is this going to impact pricing on remnant?” “Does this mean that Yahoo will focus more on remnant monetization than premium?” (not direct quotes as I couldn’t find a transcript anywhere). Hopefully I can make a good case.

Some Basic Economics of Supply & Demand

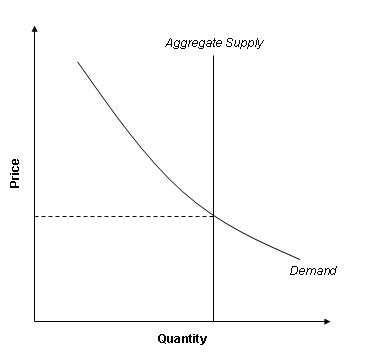

Lets start off by discussing some very basic economics — supply & demand. In today’s online advertising marketplace, supply is provided by publishers with ad inventory to sell and demand comes from advertisers and marketers that have dollars to spend. In a traditional supply and demand model suppliers have some flexibility in terms of the amount of goods that they can produce, and buyers will vary the goods they buy based on the market price. E.g., there are very many young kids that would buy an XBox for $10, but Microsoft wouldn’t put very many systems on shelves at that price. So through normal market mechanics some sort of balance price and quantity is found which in generally the intersection of the supply & demand curves. (by the way — if all of this is foreign to you, please go read this wikipedia article). Here’s an example of a traditional supply/demand curve:

Note that these graphs generally refer to the short term. E.g., think of this as a ‘snapshot’ today, or this month. Over the year, Microsoft may change the way they produce Xboxes and this might change the behavior of their entire supply curve. Also, Nintendo might come out with a competing product which pushes the demand curve down.

‘Supply’ in Online Advertising

Now, this simple model doesn’t apply to very much at all as every single product/commodity/industry is slightly different. Online advertising itself is a rather peculiar case, especially on the Supply side of things. First of all, how do we measure supply? Well, most people you ask would probably say “impressions, DUH!“. WRONG. One impression is most definitely not the same as another. A well educated male user with a high income interested in buying a car is worth a heck of a lot more than a 14 year old girl posting on her Myspace page. That’s the thing — the quality of supply changes not only per publisher, but also per user and page. Certain users are worth more… Certain pages are also worth more, not because contextual technology might work, but because the ad might be displayed more prominently, or because this is a page that users tend to stay on for a long time.

Ok, so now what? Well, theoretically we could draw out one individual supply curve for every possible combination of user quality and page, but obviously that’s not very feasible. What we can do is aggregate all of these together into a more theoretical “aggregate supply curve”. Normally aggregate supply is used when observing markets as a whole… which seems fitting here. Now, a normal aggregate supply curve is upward sloping as in the figure above — this is not the case in online advertising.

What’s interesting in online advertising is that publishers do not control the amount of inventory they have. Think about it — you’re the New York Times — is there any way that you could influence the number of visitors to your site TODAY? I guess theoretically you could advertise, but considering this isn’t very cost effective (e.g. a click costs a lot more than the impressions you’d garner), we’ll ignore this case. You could also make the argument that at a certain price the publisher should simply stop serving ads to reduce the overhead in bandwidth and various leasing fees that may come with his adserving solution. The problem is, the publisher won’t know what the price is until after he has sent the impression to his adserver, at which point you might as well serve even the cheapest ad as some money is better than nothing. So what does that mean for our supply & demand curves? Well, rather simple — we simply get a straight line, as follows:

In the graph above, the price for inventory is determined solely by demand. Note that I didn’t draw any separation on the supply side between “premium” and “remnant”. You simply can’t, because there really is no differentiation on supply based on these two factors. One impression on Yahoo! Mail’s login page for a twenty year old male might be premium one second and remnant the next. It’s not dependent on any supply factors, simply on which type of advertiser is buying the inventory. So here comes the first argument against premium & remant — inventory is deemed premium based on the buyer and has absolutely nothing to do at all with the actual ad impression beind sold.

Why is it that we would refer to them differently when the actual inventory is the same? It’s not like we can split the inventory — the same impression can be premium one day and remnant the next. So that’s the first reason why I think the market should stop thinking about “premium vs. remnant”, and instead look at overall supply.

Some Final Thoughts on ‘Supply’

One of the things that I struggled with greatly while writing this post was actually how to model supply. I was hoping to do something fancier than simply place a straight line on my graph. Why is this? Well — as I mentioned above, supply is really a function of user quality, page quality and user timing. For example, the same user on the same page is more valuable the first time he looks at it than the second. How does one forecast this? Intuitively I think people know that the growth rate in supply today is mostly in low quality inventory. Why? Well, people talk about “remnant” inventory growing with sites like Myspace, Youtube and Photobucket. This inventory has very high user frequency, generally low ages and hence is lower quality.

If someone has had some luck actually coming up with a good way to theoretically model a publisher’s supply I would love to hear it. Actually.. just post a comment!

Stay tuned for Part II — We’ll look at demand, and provide more arguments as to why the phrase “premium vs. remnant” should

never again be uttered when discussing the online advertising industry.

Related Posts:

- Adotas Premium v. Remnant Series

- Premium vs. Remnant — (Part III — Remnant)

- Premium vs. Remnant — (Part II — Demand)

- Welcome to Q2, goodbye ad revenue?

- Exchange v. Network Part II: Adoption

-

http://brontemedia.com/2007/05/10/premium-and-remnant-advertising/ Bronte Media » Premium and Remnant Advertising

-

http://www.yardley.ca/blog Greg

-

Mike

-

http://www.mikeonads.com/2007/05/16/premium-vs-remnant-%e2%80%94-part-iii-%e2%80%94-remnant/ Mike On Ads » Blog Archive » Premium vs. Remnant — (Part III — Remnant)

-

http://www.mikeonads.com/2007/08/10/adotas-premium-v-remnant-series/ Mike On Ads » Blog Archive » Adotas Premium v. Remnant Series

-

http://venturebeat.com/2007/07/30/adsdaq-one-of-the-last-indie-ad-exchanges/ VentureBeat » ADSDAQ, one of the last indie ad exchanges

-

Joydeep

-

http://scarcebits.com/?p=6 Scarcebits.com – Digital business and economics by Marc-Antoine Lacroix » Adspots: inelastic supply curve?

-

Menon

-

http://www.zip-repair.org/ Free Zip File Repair

-

Jason Cunningham